On 25 April every year Australians commemorate the landing at Gallipoli, the ultimately ill-fated campaign of the First World War designed to force the Dardanelles, take Constantinople (now Istanbul) and topple the Ottoman Empire. Around the nation, from the major cities and towns to the smallest hamlets, religious services, marches of returned veterans and speeches take place to mark Anzac Day.

A century has passed since that fateful day when the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) stormed the craggy beaches of the Gallipoli Peninsula. The narrow isthmus, heavily defended by the Turks, was their battlefield (and graveyard) for the next eight months. In one grand charge alone, at a place called Lone Pine, soldiers of the New South Wales 1st Infantry Brigade won seven Victoria Crosses. A day later the foolishly brave men of the Australian Light Horse were cut to ribbons by Turkish machine guns at a place appropriately named The Nek. The slaughter took less than three minutes and the bodies would not be buried until 1919. By then the bones of the dead had bleached the ground.

The Australians lost 8,709 killed in the Gallipoli campaign; the New Zealanders suffered even worse, in percentage terms: 2,701 dead out of the 8,556 men who served. Compared to an average campaign on the Western Front, the figures are almost paltry. Tell that to the families of the men who were killed.

While the Gallipoli failure became just another footnote in the quagmire of the First World War, 25 April 1915 came to symbolise the spirit of the nation. It was Australia’s coming of age and for many resonates more loudly than Australia Day, 26 January.

Australians often forget Gallipoli also featured the British and the French. Both suffered heavy casualties. The French don’t have an exact number; a Gallic wave of the red pen puts the official count at 10,000 dead. The British are more precise; they lost 21,255.

Another 52,230 were wounded, among them Earl Thomas Powers, my maternal grandfather. He didn’t make it past the first day. Wounded in the leg, he fell back over a ledge and was fortunate to be snagged by a tree. While the sounds of war raged around him and the smell of cordite singed his nostrils he waited 24-hours before being rescued and brought to an aid station. By then the wound had festered and gangrene was starting to set in. The medics patched him up, but his leg would never completely heal and he lived with a permanent sore for the remainder of what turned out to be a long life.

Apart from his brief and painful trip to Turkey, Earl Powers lived out his life in Burnley, a Lancashire mill town. Every Armistice Day for more than half a century he would play the ‘Last Post’ on a trumpet at the Cenotaph in Towneley Hall, Burnley’s grand mediaeval tourist attraction.

The overall commander of the expedition, General Sir Ian Hamilton- a fine man, but the wrong one for Gallipoli- concluded one of his dispatches to the imperious Minister of War, Lord Kitchener: ‘This morning, the 10th Division captured a trench.’ Three years later and it is possible, indeed probable, front-line commanders on the Western Front were sending similar messages back to their headquarters.

After Gallipoli, the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) – the only completely volunteer army serving on the Western Front in 1918- entered the new slaughterhouse. They fought and died in battles such as the Somme, Pozieres, Bapaume, Arras, Bullecourt, Messines, Ypres, Hamel, the Marne, Amiens, Passchendaele and many others. Over 46,000 died in France; more than 11,000 have no known grave. It’s hard to imagine almost a quarter have never been identified. I suppose that’s what happens when you mix artillery shells with Flanders mud.

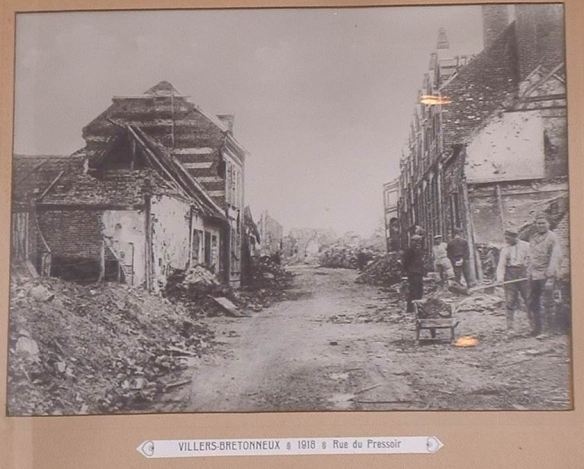

Villers-Bretonneux, a little French village on the train line not far from Amiens, is the antithesis of Gallipoli. During 1918 it was the site of Australian victories against overwhelming odds and the carefully tended Australian War Memorial here (maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) is the nation’s principal First World War memorial.

The Germans advanced in March 1918 but were halted by stiff Australian resistance. They attacked in strength again in late April and took the town. The Australians retook it three days later. Between April and August four Australians won the Victoria Cross, one, Lieutenant Cliff Sadlier, on Anzac Day, 25 April. Lieutenant Albert Borella MM won his in mid-July while Lieutenant Alfred Gaby was awarded the medal posthumously for his actions on 8 August. He was killed three days later when walking along the line encouraging his men during another attack.

When my sister, youngest nephew and I visited Villers-Bretonneux in July 2004 we arrived by train in the early morning. The residents were only just beginning to stir as we trudged through the town, heading for the War Memorial.

Long before you reach the memorial, the central tower is clearly visible, standing stark in the countryside, surrounded by fresh green and gold fields you imagine Van Gogh would have happily spent days trying to paint, with or without his ear.

Looking at this typically rural landscape it is hard to imagine that at this time in 1918 it was not much better than a mud heap, the trees stripped of their foliage by shrapnel, the farmhouses mere rubble, no longer habitable. It’s hard to imagine it in colour. Photographs of the First World War are black and white, stark and Gothic, betraying no hint of the Impressionist splash of nature’s lively colours.

When referring to the appalling casualty figures the language of writers, poets and journalists tends towards phrases that include the term the ‘flower of youth’. Tens of thousands of the dead were just that, youths, many still in their teens. Yet it is easy to forget the older males, the family men and fathers, who paid the ultimate price.

Buried in Villers-Bretonneux are at least two men in their forties. The headstones are spare and functional, giving little hint of the person being honoured. ‘Private J. Hall, killed 30 March 1918, aged 43.’ For J. K. McDowell, a winner of the Military Medal, who was killed on 26 May 1918 at the age of 46 the headstone adds, ‘Sadly missed by his sorrowing wife and family’.

Another reads: Lieutenant Hugh McCall, killed 12 August 1918, aged 29. ‘James H. McCall, father with wife and daughter visited this grave August 25, 1923 bringing loving remembrances from family and friends in Australia.’ It is almost impossible to imagine the emotion behind that poignant gravestone.

Then there are those who lost their lives after the 11 November armistice. Sapper H. Long, of the Australian Engineers, was killed on 25 November 1918; Private G. Mara a day later.

The war transcended religion as well as age. The headstone for M. Marks of the 35th Battalion notes his date of death and age: 8 August 1918, aged 18. Inscribed beneath these cursory details is the Star of David.

Other headstones note the burial site of an unknown soldier with the words: ‘A soldier of the Great War. An Australian regiment.’ There are British, South African, and Canadian soldiers buried here as well, including 17-year-old Private W. Jondrow, killed on 10 August 1918.

On the cream-coloured winged walls flanking the central tower are the names of the 11,000 men for whom there is no known grave. Little red paper flowers add a light touch of colour. The flowers have been inserted into the cracks by previous visitors: one next to W. A. Michie of the 45th Infantry Battalion, another alongside R. D. McLennan of the 47th Battalion. That day there were six others so blessed.

Beneath the names of members of the 52nd Battalion was a wooden cross inscribed ‘St. Stanislaus College, Bathurst’. A school excursion from rural New South Wales to rural France I imagine.

In 1998 the Australian Rugby Union team (known as the Wallabies) was in France to play one Test match. They made a special visit to the memorial at Villers-Bretonneux and later attended a reception at the town hall where the mayor praised the efforts of Australian soldiers 80 years earlier.

Coach Rod Macqueen later said, “It was a moving moment, reading the names and the ages of the Australians who had fought and died on foreign soil. Many were in their late teens and were younger than those in our touring party. We had arranged the visit with a special purpose in mind. We wanted to raise…in the minds of the players the honour of playing for their country…I think it left an indelible mark which was to surface later in the determination and courage of the team.” The Wallabies went on to defeat France 32-21. In fact they won 15 of their next 17 matches, including the 1999 World Cup.

As the Wallabies prepared to go out on the field to play France in the final of that World Cup, Macqueen read his players an extract from the diary of Lieutenant Bethune, commander of a section of the 3rd Machine Gun Company who were preparing to defend Villers-Bretonneux against a German attack in March 1918. Bethune made six points, among them were: 1. This section will be held, and the section will remain here until relieved; 2. The enemy cannot be allowed to interfere with this program; 3. If the section cannot remain here alive, it will remain here dead, but in any case it will remain here. Bethune’s sixth and final point was ‘the position, as stated, will be held.’ The Wallabies proceeded to rout the French 35-12.

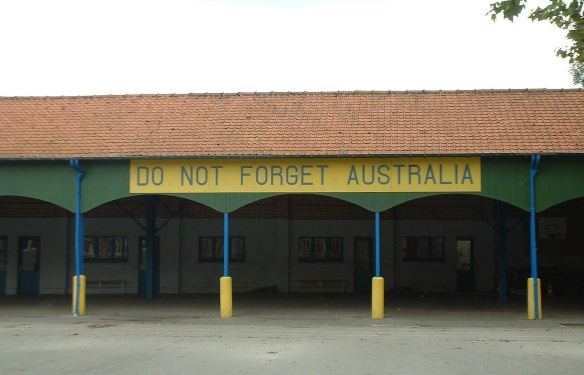

The Australian influence in Villers-Bretonneux is unmistakable: from the Restaurant le Kangourou, the cafes with signs outside bearing koalas, the streets with names such as the Rue de Melbourne and the Rue Victoria, where the Ecole Primairie Victoria (Victorian Primary School) is situated, to the police station with kangaroo motifs embedded in stone above the entrance. Money donated by people in Victoria after the war helped rebuild Villers-Bretonneux.

The Australian influence in Villers-Bretonneux is unmistakable: from the Restaurant le Kangourou, the cafes with signs outside bearing koalas, the streets with names such as the Rue de Melbourne and the Rue Victoria, where the Ecole Primairie Victoria (Victorian Primary School) is situated, to the police station with kangaroo motifs embedded in stone above the entrance. Money donated by people in Victoria after the war helped rebuild Villers-Bretonneux.

We had lunch in Chez Remy, a small brasserie opposite the memorial park in town. The maitre d’ was a thick-set man in his forties with a bad comb-over and handle-bar moustache, wearing an orange T-shirt and black leather pants. He looked like the president of the local chapter of the Village People fan club.

We had lunch in Chez Remy, a small brasserie opposite the memorial park in town. The maitre d’ was a thick-set man in his forties with a bad comb-over and handle-bar moustache, wearing an orange T-shirt and black leather pants. He looked like the president of the local chapter of the Village People fan club.

On the back wall was a small Australian flag, some Australian postcards and a cabinet with ‘Australian’s presents’ inside: coins and stitch badges mainly. The toilet was a Thai-style squat hole in the ground, a reminder we were in a rustic part of the French countryside. It may well have been in service back in 1918.

In the war museum on the Rue Victoria the walls have large, framed, black and white photos of Australians in and out of action. It’s noticeable how many of the men photographed are smoking. Lung cancer was the least of their worries.

There are detailed colour maps and diagrams of the fighting in the Somme area and a bookcase filled with reading material, a cornucopia of Australiana including C.E.W. Bean’s Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 as well as the more prosaic Australia 1964; Birds of Australia; and Fairholme: the First 75 Years 1917-1992.

I spoke briefly with an Australian couple visiting the museum. Aged in their 50’s the man recalled, “My father had me late in life and he fought around here. He wouldn’t talk much about it. He was with the 22nd Battalion and I’ve got his diary. He’d been at Gallipoli and then Egypt and came to France.”

His wife added, “He reckoned this was worse than Gallipoli. The mud and the cold and the trenches.”

It’s impossible to come away from Villers-Bretonneux and not feel a mixture of intense national pride tempered by a wretched sorrow at the destruction of so many lives. All told, the nation lost 60,284 men killed. This out of the 331,781 who went overseas on active service. Another 153,000 were wounded. It was a terrible toll. Australia gained northern New Guinea and the islands of the Bismarck Archipelago for its trouble.

While the survivors of that terrible war are now gone and the veterans of the equally ferocious Second World War diminish each year, Anzac Day lives on and, especially in recent years, draws ever more converts.

Australia may have become a nation in 1901, yet its sense of unity and purpose was not forged until the Homeric tragedy of the Dardanelles. If Gallipoli was the forge that gave the steel to a nation, Villers-Brettonneux tempered that steel.

The volunteers were not warmongers, nor professional soldiers; they were part of an attitude and an ideal that may have long expired in our society. The attitudes have long since changed and the ideals may have been flawed, but their courage was unmatched and their sacrifice is part of what makes Australia and Australians a great and justifiably proud nation. Perhaps that’s why almost a century later a freshly-painted sign in the Villers-Bretonneux primary school proclaims: ‘Do Not Forget Australia’.